‘You look past the print to the inner meaning’: On photographer Dorothea Lange and her 3 most iconic images

November 30, 2010 at 20:23 , by admin

This essay is about Dorothea Lange’s contribution as a photographer during the Great Depression. It was written for my History of Photography course at Ryerson University and touches on the biographical details of her youth that were important in her development as a photographer, documenting the plight of migrant workers from the Dust Bowl region of the U.S. Midwest.

This essay is about Dorothea Lange’s contribution as a photographer during the Great Depression. It was written for my History of Photography course at Ryerson University and touches on the biographical details of her youth that were important in her development as a photographer, documenting the plight of migrant workers from the Dust Bowl region of the U.S. Midwest.

The piece examines three of Lange’s iconic photographs from the Depression: White Angel Bread Line, Man Beside Wheelbarrow and Migrant Mother. There were many others to choose from that period, but these three exemplify her abilities as a socially concerned photographer.

First and foremost, Lange was visionary, compassionate and wanted to change the world, qualities that enabled her to produce a collection of photographs that in combination with text — much of which was supplied by her partner, Paul Taylor — changed government policy and helped the needy. They were the reasons her photographs were held in such high regard even to this day.

Lange was born on May 25, 1895, in Hoboken, N.J., to German parents, Joan and Henry Nutzhorn. A severe bout of polio at seven and the sudden abandonment by Lange’s father of the family when she was 12, were two major events that shaped her outlook both as a woman and a photographer.1

Lange’s childhood illness affected her right leg, leaving her with a permanent limp that made her self-conscious and filled with self-doubt throughout her adolescent years. But it also made her more empathetic, especially when it came to society’s marginalized people.

“It perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me. It informed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me. All those things at once,” she said. “I’ve never gotten over it and I am aware of the force and the power of it.”2

But years later her handicap would also become a useful tool of sympathy that she would use to gain access to her subjects.3

“[My handicap] truly opened doors for me,” she said.4

Lange’s second life-altering event — her father walking out on the family — forced her mother to move herself and her two children to live with her own mother, Sophie, and take a clerical job across the Hudson River in the Big Apple with the New York City Public Library.

‘You can’t deny what you must do’

For reasons likely of convenience, Lange accompanied her mother to New York to attend elementary school at Public School 62 in 1907. According to family friend and author Elizabeth Partridge, Lange would spend her after-school hours looking at picture books at the library while waiting for her mother to finish work, and adopted what she later described as a “cloak of invisibility” whenever she had to pass through the Bowery, a rough section of the Lower East Side where she witnessed almost daily many drunkards, prostitutes and destitute people.5 She would use this cloak when photographing many of her subjects in migrant camps and other people, Lange said.6

When she was nearing high-school graduation, Lange told her mother that she wanted to become a photographer even though she had never held a camera. Her mother and grandmother insisted that she do something practical and that she enrol in teachers college, which she did at the New York Training School for Teachers in 1914. Still no less deterred, Lange apprenticed in the evenings after classes with several portrait photographers, including Arnold Genthe and Aram Kazanjian.

“You can’t deny what you must do,” she said.7

It was at these portrait studios where she learned camera techniques and successful business practices.

Her training in photography also included a course at Columbia University with Clarence White. Although she never completed any of his assignments, she later credited the “skilled teacher” with giving her “a nudge here, a nudge there.”8

It was not surprising when Lange quickly abandoned the idea of teaching after a distastrous episode with unruly grade-school students who she couldn’t control during a class.

Early career: portraiture

In 1918, she decided to see the world and got as far as San Francisco with her school chum Fronsie Alstrom before a pick-pocketing incident left them virtually penniless and ended their trip. Lange immediately found work in the city at a general store that also did photo finishing. That was where she met a client, Roi Partridge, who was then married to the photographer Imogen Cunningham. The three became fast friends and the couple introduced Lange to their Bohemian circle of artists, which included Maynard Dixon, a flamboyant illustrator and painter, who Lange would marry in March 1920.

In 1918, she decided to see the world and got as far as San Francisco with her school chum Fronsie Alstrom before a pick-pocketing incident left them virtually penniless and ended their trip. Lange immediately found work in the city at a general store that also did photo finishing. That was where she met a client, Roi Partridge, who was then married to the photographer Imogen Cunningham. The three became fast friends and the couple introduced Lange to their Bohemian circle of artists, which included Maynard Dixon, a flamboyant illustrator and painter, who Lange would marry in March 1920.

A year before her marriage, Lange opened her own portrait studio with a $3,000 loan from an enthusiastic investor. Like many female photographers of her time, she made a living taking portraits of wealthy women and their families.9 Her photographs, taken with a 31/4 x 41/4 Graflex camera, were influenced by Pictorialists.10 She was, in fact, a founding member of the Pictorial Photographic Society of San Francisco in 1920. Author Pierre Borhan wrote that Lange at that time did not have “a strongly original style, nor did she aspire to have a place in the ’star system.’”11

At the time, she did not consider herself an artist.

“People like Imogen Cunningham, whom I knew very well by that time, worked for name and prestige,” she said. “But I was a tradesman.”12

Her early commercial work featured only the client’s face with no hint of the surroundings; an environmental portrait it was not.

“Good meant to me being useful, filling a need, really pleasing the people for whom I was working,” she said “My personal interpretation was second to the need of the other fellow.”13

During those years, Lange was often a difficult stepmother to Dixon’s daughter Constance from a previous marriage and later she was a conflicted career mother to two of her own children, John and Daniel, whom she would leave for long stretches of time with other families.

She was, however, contented for a while in the 1920s to just run a studio and make a nice home with her husband and their children. But ultimately she grew dissatisfied with her career and marriage in the early 1930s, enough to restructure her entire life.

During this growing restlessness, Lange had an epiphany while on summer vacation in 1929 in Phoenix. It occurred to her that she would photograph only people. Her friends at the time, Cunningham and Ansel Adams, were focused on botanical plants and landscapes, respectively.

“What I had to do was to take pictures and concentrate upon people, only people, all kinds of people, people who paid me and people who didn’t,” Lange said.14

The Depression

That realization of herself came shortly before the U.S. stock market crashed later that fall, which resulted in millions of unemployed people often living on the streets of America. Some of them, in fact, would hang around outside Lange’s studio. By 1933, the severity of the country’s economic slump became such a concern for Lange that she felt obligated to go out into the streets and document the dire living conditions of the people.15

The Depression affected Lange personally as well. Commissions for her work were fewer, forcing her and Dixon to live separately in their own studios and to board their sons at school to save money, although marital strains were also a deciding factor in that arrangement.

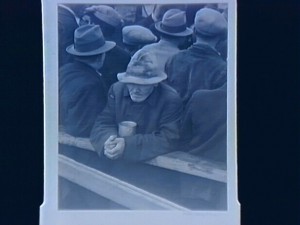

The work that marked her transition to documentary photography from portraiture in 1933 was the photographs of a scene at a soup kitchen run by a wealthy woman, who people called the White Angel.16 Lange made 12 exposures with a Graflex, including several of a down-in-the-dumps man waiting in a lineup for food with a tin can in his hands. Author Milton Meltzer wrote that in the studio Lange was concerned with how best to arrange her subjects, but in the streets her immediate concern was about the situation.17

She hung one of those prints on a wall in her studio, and some of her visiting clients would ask her what she planned to do with it. For some time, she said she didn’t know. Years later, Lange said, “don’t let the question stop you, because ways open that are unpredictable, if you pursue them far enough.”18

The photo of that man, which came to be known as the White Angel Bread Line, would later be considered one of the best images depicting the Great Depression, an era when one-in-four households had no work or government aid, Meltzer wrote.19

Another photograph by Lange that also depicted the Depression so well was Man Beside Wheelbarrow of another defeated man in 1934.

“Five years earlier, I would have thought it enough to take a picture of a man, no more,” Lange said. “But now, I wanted to take a picture of a man as he stood in his world; in this case, a man with his head down, with his back against the wall, with his livelihood, like the wheelbarrow, overturned.”20

Lange’s bread line photographs led to an exhibit at Brockhurst Gallery in Oakland, Calif., where they were seen by a labour economist and professor, Paul Taylor, who eagerly used one of the images to accompany his Survey Graphic article published in September 1934.

By that year, Lange was pursuing her passion for independent photography and people were referring to her as the first “documentary photographer,” Meltzer wrote.21 However, that is untrue, considering years earlier Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis had documented child labour practices and poor living conditions in the slums of New York City, respectively.22

In Taylor, Lange found her champion, an intellectual with connections, who himself was examining the challenges facing migrant labourers for the government and who personally believed in the power of pictures.

“No amount or quality of words could alone convey what the situation was that I was studying,” he said.23

Taylor also was charmed and impressed enough with Lange to help her get freelance work, documenting rural migrants with the State Emergency Relief Administration (SERA), whose task was to find ways to help poor farm workers travelling west to California in search of work after a series of 1933 droughts and dust storms ruined their livelihood in the Midwest. Taylor’s report was eventually read by two key federal government officials, Rexford Tugwell and Roy Stryker, the head of the Resettlement Administration’s historical section, which was renamed the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1937. They were impressed enough with Lange’s work to hire her in September 1935 at an annual salary of $2,300 US to work for FSA.

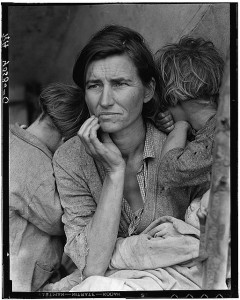

Migrant mother

That year, Lange was 40 years old and ending her marriage to Dixon, closing her portrait studio and beginning her life as a documentary photographer and wife of Taylor.

Lange’s new work focus would eventually take her all over California and neighbouring states, wherever migrants roamed until 1940 when Stryker let her go due to budget cuts. Her most famous picture came in the winter of 1936 from five exposures that she made of a poor mother, Florence Owens Thompson, and her hungry children at a pea pickers camp in Nipomo, Calif., a place that Lange nearly passed up after an exhausting day of photography.24

After processing the film Lange submitted them for publication at the San Francisco News as well as sending them to Washington, D.C.-based FSA. The Migrant Mother photograph also accompanied a report by Taylor for Survey Graphic in September 1936.25

The power of that photograph and other ones made by Lange laid in her the “use of provocative gesture,” Ryerson instructor Iain Cameron said during a lecture. That obviously was drawn from her experience as a portrait photographer. In the case of Migrant Mother, Lange captured the relatively young mother’s haggard appearance with a closeup shot, using the woman’s hand and facial expression to convey the trouble that she was encountering, author Naomi Rosenblum wrote.26

When that picture was publicized Americans were outraged that their own people were starving. It was a watershed moment, considering government officials earmarked money for the construction of two migrant camps to provide clean water and housing. More photo assignments led to other governmental interventions, such as the construction of an additional 20-odd camps, programs for farm loans and other projects.

To borrow an advertising phrase, the Migrant Mother photograph had legs because it went on to be the most reproduced image of any of the 270,000 FSA photographs and has come to define the Depression era.27 Even her boss Stryker acknowledged that it was “the picture” of FSA.28

Lange by no means was the only photographer documenting migrants at the time. FSA had photographers Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn and Walker Evans on the payroll as well.

The success of the photograph bothered Lange too.

“I don’t understand it,” she said. “It seems to me that I see things as good as that all the time.”29

It is worth noting that the presence of a thumb in Lange’s Migrant Mother picture bothered her so much that she broke into the office where her negatives were stored to scratch out its existence, an act that irked Stryker, Cameron said.

Many Lange biographers have noted that her peers considered her camera and darkroom techniques to be poor. Homer Page said she was technically “inept” and “clumsy.”30 Ron Partridge said she wasn’t a good printer and wasn’t interested in investigating the process.31 Lange herself spoke of the “terrors of the darkroom” and that photography was “a gambler’s game.”32

In letters to Stryker, Lange blamed her working conditions in the field on the quality of her negatives and prints. But he questioned that since Rothstein and Evans were working in the field under the same hot weather conditions without any deterioration in their work.33

For technical assistance, Lange relied on photography assistants and even her friend, Adams who processed and printed some of her work.34

This, however, didn’t matter because the significance of the subject matter of her work, in other words, the content, trumped technical or aesthetic considerations, critics said. Despite her technical shortcomings, Ansel Adams said “she was both a humanitarian and an artist.”35 Pare Lorentz wrote in an essay published by U.S. Camera that Lange and John Steinbeck, author of The Grapes of Wrath, did more for rural migrants than any politician did in those years.36

Lange said, “the print is not the object; the object is the emotion the print gives us. You look past the print to the inner meaning.”37

And everyone did.

Comments Off

Category Photography, Photojournalism, documentary / Tags: /

Social Networks : Technorati, Stumble it!, Digg, delicious, Google, Twitter, Yahoo, reddit, Blogmarks, Ma.gnolia.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.